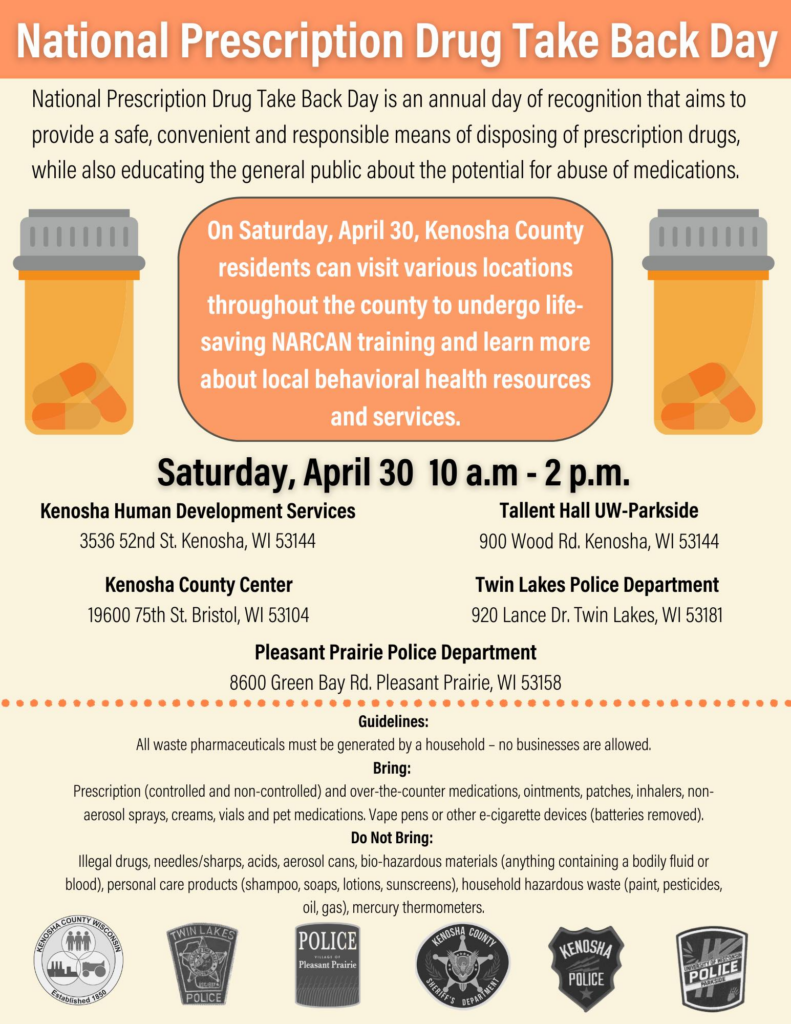

Mark your calendar! National Prescription Drug Take Back Day is April 30, 2022, from 10 AM – 2 PM.

Mark your calendar! National Prescription Drug Take Back Day is April 30, 2022, from 10 AM – 2 PM.

Prescriptions can be dropped off at:

Kenosha Human Development Services

3536 52nd St., Kenosha

Tallent Hall UW-Parkside

900 Wood Rd., Kenosha

Kenosha County Center

19600 75th St., Bristol

Twin Lakes Police Department

920 Lance Dr., Twin Lakes

Pleasant Prairie Police Department

8600 Green Bay Rd., Pleasant Prairie

Stigma is defined as “a mark of disgrace that sets a person apart from others.” Ample time and resources have been expended in explaining the proper language to use when talking to and about those with substance use disorders, mental illness, and all those other-isms, but stigma is still inescapable. Why? How long before we need to understand that the language we use is killing people?

Stigma is defined as “a mark of disgrace that sets a person apart from others.” Ample time and resources have been expended in explaining the proper language to use when talking to and about those with substance use disorders, mental illness, and all those other-isms, but stigma is still inescapable. Why? How long before we need to understand that the language we use is killing people?

The Kenosha County Substance Abuse Coalition has spent a considerable amount of time working to reduce stigma around substance use disorders. Still, day in and day out I see reminders that we have a lot of work to do. Most recently I read about a truly kind woman who bought a meal for a woman who was homeless. The post ended this way: “So next time u judge a homeless person think twice…not all of them are homeless because of a drug addiction or because they are lazy.”

The Kenosha County Substance Abuse Coalition has spent a considerable amount of time working to reduce stigma around substance use disorders. Still, day in and day out I see reminders that we have a lot of work to do. Most recently I read about a truly kind woman who bought a meal for a woman who was homeless. The post ended this way: “So next time u judge a homeless person think twice…not all of them are homeless because of a drug addiction or because they are lazy.” Addiction is considered a family disease because of its wholly negative impact on the family and other loved ones.

Addiction is considered a family disease because of its wholly negative impact on the family and other loved ones.